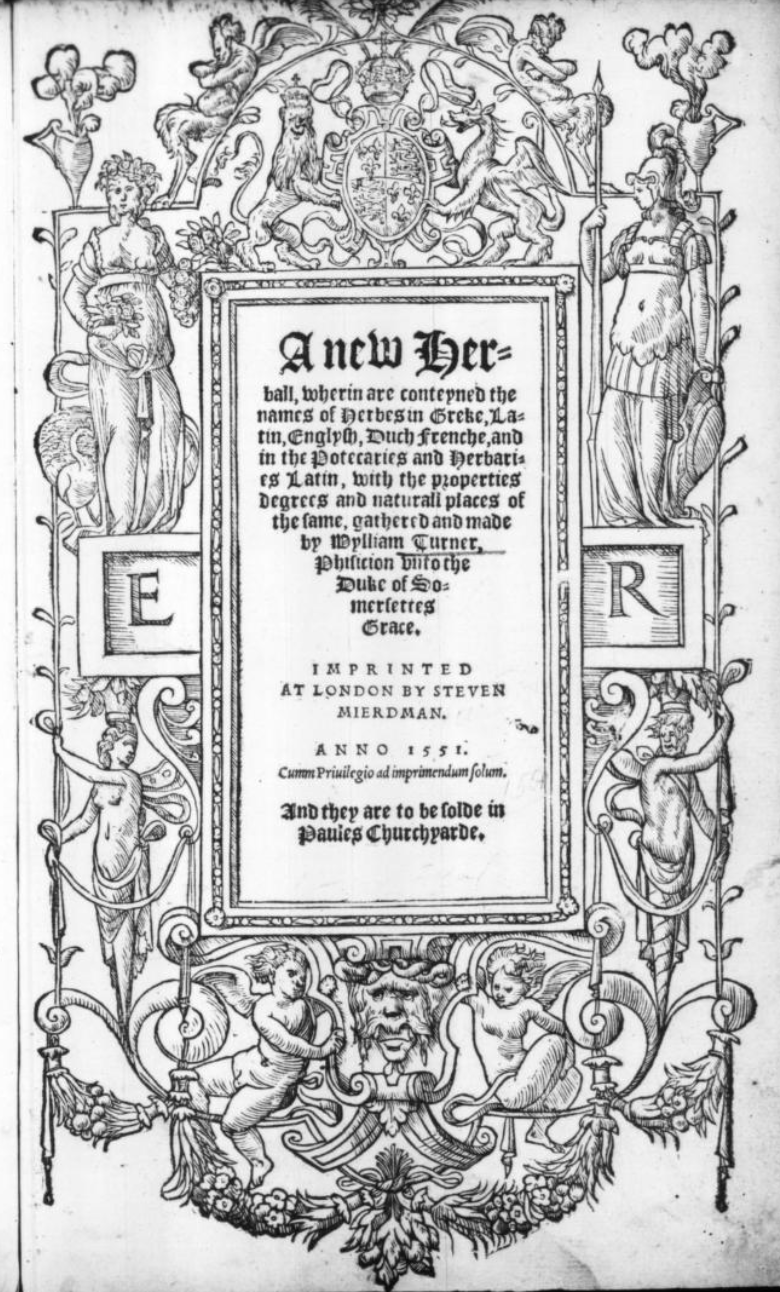

A new herball by Willam Turner

Over A new herball by Willam Turner

This is how this book begins, the rest of it is in original and normal English. A new herball, wherin are conteyned the names of Herbes in Greke, Latin, English, Dutch, Frenche, with the properties degrees and naturall places of the same, etc.

The prologue and the beautifully calligraphed first letters and the image are not displayed; it's too long. Many letters look a bit strange. Therefore, this is being improved as much as possible, otherwise you'll see this: Here are thꝛe kyndes of Wozmwode, ponticum, marinum, and ſantonicum. Ponticum abſinthium;whych maye be named in engliſh, woꝛmwode gentle oꝛ woꝛmwode Romane, woꝛmwod pon tyke groweth in no place ol Englande, that euer J coulde ſe, ſauing only in my loꝛdes gardyne at Syon, a that Jbzought out of Germany, foꝛ thoſe ij. kindes of woꝛmwode which diuerſe take foꝛ pontyke woꝛm wode, are none ol põtike wozmwod, Some take p como great leued woꝛm wode which gro weth almoſt in euery place, tobe põtyke woꝛmwode.

|

Of Wormwode. Absinthium is named in greke Apsinthion, because no beast wil touch it for bitternes, in Englis wormwode, because it killeth wormes, I suppose that it was ones called worme crout, for in some part of Fresland (from whence semeth a great part of our englysh tonge to have come) it is so called even unto this daye; in duche wermut, in frenche aluine or absence. The kyndes and the places where they growe. There are the kyndes of Wormwode, ponticum, marinum, and santonicum. Ponticum absinthium, which maye be named in English, wormwode gentle of wormwode Romane. Wormwood pontyke groweth in no place of Englande, that ever I coulde se, saving only in my lords gardyene at Syon, that I brought out of Germany, are none of pontyke wormwood. Some take that common great leaved wormwode which growth almost in every place, to be pontyke wormwode. But they are far deceived, for Galene in II, boke of methodus medendische weth plainly in these words that folowe, that this great leaved and stynkynge wormwood is not the true pontyke wormwood. When as ther is in every wormwode a duble poure, in pontike wormwode is there no smaller astringet propertie, ther is in al other wormwodes a very vehement bitter qualite. But astriction, which a man can perceive by tast, is ether very evyll to be founde, or els there is none to be found at all. Wherefore Pontyke Wormwode ought te be schosen out, for inflammations of the lyver. But it hath both a lese floure, lese then the other Wormwodes have. The savour of this is not only not unpleasant, but also resembleth in savour a certain kind of swete spice. The other kindes have a stinking savour. Wherefore ye must use these kyndes, and use pontyke wormwode. Thus farr hath Galene spoken. By whose words it is evident that this our common great leaved wormwood is not pontike wormwood. Als for this great common wormwood it is called in latin Absinthium rusticum, that is bouris or pesantes wormwode. Some take and use this wormwode that growth by the sea side for wormwode pontyke. But they are far deceived for the qualities of it answer nothing unto the qualyties of wormwode pontyke in Galene, this same wormwood is the right Absinthium marinum or seryphum of Dioscorides and Plini, which may be called in Englysh sea wormwood, Plini writeth of the growing place of this herbe thus lib. Trisesmo secondo, capite nono. Nascitur er in mari ipso Absinthium, quod aliqui Seriphum uocare, circa Taposirim, et caeter. This growth in the sea it selfe wormwood, which some call Seriphum, beside Taposyris of Egipt. Dioscorides saith that it growth in the mountain Taurus. In oure tyme it is plenteouslye founde in England about Lynne and holly Ilond in Northumberland, and at Barrouwe in Brabant, and at Norden in east Freslande. Fuchsius is to be excused, whyche toke Argentariam Herbariorum, wyth longe smalle coddes to be Absynthium marinum, because he never sawe the sea in all hys lyfe where as thys herbe doth comonly growe. As concernyng Wormwoode Pontyke from which we have by occasion geven, some thing dysgressed; I will shortly shew you, what my minde is oft it. I thynke verelye that Absinthium Romanum of Mesue is, Dioscorides; Absinthium Ponticum, that same have I sene of late many tymes. I had it from Rome, and it growth about templum pacis, and also about the walles in diverse places, a kynde of that, is much in Germany and in Brabant, about Colen it is called grave crowt, because they set it upon their frendes graves and freses call it wyld Rosmary. The Pothecaryes of Anwerpe Absinthium Romanum. How be it, there is some difference between it, that growth in Rome, and it that growth in Germanye. It that growth in Germanye, hath lesse leaves, grener and thinner then it whyche growth in Rome, and also a pleasanter savour. It that groweth in Rome hath thycke, whyter and bygger leuves, then it of Germany, they are also hoter and of a stronger smell. As for it that growth in Germany, I have proved oft tyms that it hath perfyctly done such thynges als pertayne unto Wormwod Pontyke. Thys herbe is not founde in Germany of hys owen settinge or sowynge in the feldes, but is only in gardynes, where as it is planted or set by mannes hands. The thyrde kynde of Wormwood is called Absinthium Santonicum. I have not sene it in Englande ofter than ones, that ever I remembre, it maye be called well in Englysh French wormwode, because is hath the name of a certain regyon of France, whose inhabyters are called Santones. The degree. Pontike Wormwoode is hote in the first degree and drye in the thirde after Galene, Aetus, and Palus agmeta, but after Mesue it is drye, but in the second degree, but more credence is to be gevene unto Galene then to mesue. Sea wormwoode is, as Aegineta writeth hote in the first degree, and drye in the first. Frenche Wormwode is weker then sea Wormwode in breaking of humours, in hete and in dryures. The iuice of Pontyke Wormworde is rekened of all substandy all autores more hote a good dele then the leaves are. The properties of wormwode. Wormwode hath astringent or binding together, bytter and byting qualitees, hetinge and scouring away, strengthning and drying. Therefore is dryveth furth by the stoole and urine also cholerike and gallische humores out of the stomack, but it avoideth most chefely the gall or choler, that is in the urines. Thus writeth Galene: Wormwood maketh one pisse well, drunken with syler mountayene and Frenche spycknarde. It is good for the winde and payne of the stomake, the belly. It driveth away lothsummes. The broth that is soden or steeped in, dronkenne every daie about v. unces, heleth Jawndes or gulesouyght. It provoketh womens floures, ether taken in, or laid to without with honey, it remedyeth the stranglynge that cometh of eating of todestolles, if it be drunken with vinegre. It is good against the poison of ixia with wyne. The quyncey maye be heyled with this herbe, if it be anointed with it, and hony and salt and natural put together. And so with water. It heleth the watering sores in the corner of the eyes. It is good for the brusynges and darcknes of the eyes with hony. And so it is for the eares, if matter runne out of them. The brothe of Wermwood with thus vapor that riseth up from it, and smoketh up, helpyth the payne of the tethe and the ears. The broth with Malvasy is good to anoynte the akynge eyes with all. With the Ciprine ointment it is good for the long disease of the stomake, with figges, vynegre, and darnelle mele it is good for the dropsy, and the syckenes of milte. Out of Plini. Wormwood helpethe digestion. With rue pepper and salt. It taketh awaye rawenesse of the stomake, old men of olde tyme gave it to purge with a pynte and a halfe of olde sea water, six drammes of sede .iii. of salt with two unces of honey and .ii. drammes. in the Jawndes it is dronkene with rawe persly or Venus heyr. It is good for the Clearnes of the sight, it heyleth freshe woundes before there come anye water in them. Layd amonge clothes it dryveth the mothes away. The smoke of it, dryveth away gnates or mydges. If the ynke be tempered with this Juce it maketh the myse they wylle not eat the paper, that is written with that ynke. The ashes of it with rose ointment maketh blacke heare. The quantyte out of Meseus. Ye maye take of the brothe or of the stepyng of Wormmode from v. unces, to viii. of the Juce, from the drammes to .iiii. of the powder from.ij.drammes tot iii. and so will it make a purgation. But because it worketh but weykly, by it selve ye maye take it with whay, withRasynes, the stones taken out, or with roses or fumitory. Sea Wormode is not to be used for the right Wormwode, for it is noysume unto the stomake, als Dioscorides and Gale do testyfye. Nether is the common Wormwode to be taken for the right, if it maye be had. |

Of Wormwood. Absinthium is named in Greek Absinthion, because no beast will touch it for bitterness, in Englis wormwood because it killed worms, I suppose that it was ones called worm croute, for in some part of Friesland (from whence seem a great part of our English tong to have come) it is so called even unto this day; in German wermut, in French aluine or absence. The kinds and the places where they grow. There are the kinds of Wormwood, Absinthium of Artemisia ponticum, marinum and santonicum. Ponticum absinthium, which may be named in English, wormwood gentle of wormwood Romane. Wormwood ponticum growth in no place of England that ever I could see, saving only in my lord’s garden at Sion that I brought out of Germany, are none of ponticum wormwood. Some take that common great leaved wormwood which grow almost in every place, to be ponticum wormwood. But they are far deceived, for Galene in II, boke of methodus medendische wet plainly in these words that follow, that this great leaved and stinking wormwood is not the true ponticum wormwood. When as there is in every wormwood a double power, in ponticum wormwood is there no smaller astringent property, there is in al other wormwood a very vehement bitter quality. But astriction, which a man can perceive by taste, is ether very evil to be found or else there is none to be found at all. Wherefore Ponticum Wormwood ought to be chosen out, for inflammations of the liver. But it hath a lese flower, lese then the other Wormwoods have. The savor of this is not only not unpleasant but also resembled in savor a certain kind of sweet spice. The other kinds have a stinking savor. Wherefore ye must use these kinds and use ponticum wormwood. Thus far hath Galene spoken. By whose words it is evident that this our common great leaved wormwood is not ponticum wormwood. Als for this great common wormwood it is called in Latin Absinthium rusticum, that is bowers or peasants’ wormwood. Some take and use this wormwood that growth by the seaside for wormwood ponticum. But they are far deceived for the qualities of it answer nothing unto the qualities of wormwood ponticum in Galene, this same wormwood is the right Absinthium marinum or seriphum of Dioscorides and Plini, which may be called in English sea wormwood, Plini writh of the growing place of this herb thus lib. Trisesmo secondo, capite nono. Nascitur er in mari ipso Absinthium, quod aliqui Seriphum vocare, circa Taposirim, etcetera. This growth in the sea itself wormwood, which some call Seriphum, beside Taposiris of Egypt. Dioscorides saith that it growth in the mountain Taurus. In our time it is plenteously found in England about Lynne and holly island in Northumberland, and at Barrouwe (?) in Brabant, and at Norden in east Friesland. Fuchsius is to be excused, which toke Argentariam Herbariorum, with long small cod to be Absinthium marinum, because he never saw the sea in all his life whereas this herb doth commonly grow. As concerning Wormwood Ponticum from which we have by occasion given, something digressed; I will shortly shew you, what my mind is oft it. I think verily that Absinthium Romanum of Mesue is, Dioscorides; Absinthium Ponticum, that same have I seen of late many times. I had it from Rome, and it growth about temple pacis, and also about the walls in diverse places, a kind of that, is much in Germany and in Brabant, about Colen it is called grave crowt, because they set it upon their friend’s graves and freres call it wild Rosmary. The Pothecaries of Antwerp Absinthium Romanum. How be it, there is some difference between it, that growth in Rome, and it that growth in Germany. It that growth in Germany, hath les leaves, greener and thinner than it which growth in Rome, and also a pleasanter savor. It that growth in Rome hath tikke, whiter and bigger leaves, then it of Germany, they are also shorter and of a stronger smell. As for it that growth in Germany, I have proved oft times that it hath perfectly done such things as pertain unto Wormwood Ponticum. Thys herb is not found in Germany of his own setting or sowing in the fields but is only in gardens whereas it is planted or set by man’s hands. The third kind of Wormwood is called Absinthium Santonicum. I have not seen it in England often than ones, that ever I remember, it may be called well in English French wormwood because is hath the name of a certain region of France, whose inhibiters are called Santones. The degree. Ponticum wormwood is hot in the first degree and dry in the third after Galene, Aetius, and Palus Aegineta, but after Mesue it is dry, but in the second degree, but more credence is to be given unto Galene then to Mesue. Sea wormwood is, as Aegineta write hot in the first degree, and dry in the first. Frenche wormwood is weaker than sea wormwood in breaking of humors, in hot and in dryer. The juice of Ponticum wormwood is reknit of all substances of all authors mor hot a good deal then the leaves are. The properties of wormwood. Wormwood hath astringent or binding together, bitter and biting qualities, heating and scouring away, strengthening and drying. Therefore, is drive furth by the stool and urine also choleric and gallize humors out of the stomach, but it avoided most chiefly the gall or choler, that is in the urines. Thus write Galene: Wormwood maketh one piss well, drunken with siler mountain and Frenche spikenard. It is good for the wind and pain of the stomach, the belly. It drives away loathsome. The broth that is sodden or steeped in, drunken every day about v once, health jaundice or gules sought. It provoked women’s flowers, ether taken in or laid to without with honey, it remedied the strangling that cometh of eating of toadstools, if it be drunken with vinegar. It is good against the poison of Ixia with wine. The quinsy may be heled with this herb, if it be anointed with it, and honey and salt and natural put together. And so, with water. It health the watering sores in the corner of the eyes. It is good for the brushings and darkness of the eyes with honey. And so it is for the ears, if matter run out of them. The broth of wormwood with thus vapor that rise up from it, and smoked up, helped the pain of the teethe and the ears. The broth with Malvasia is good to anoint the aching eyes with all. With the Cyprinus ointment it is good for the long disease of the stomach, with figs, vinegar and darnel mele it is good for the dropsy, and the sickness of milt. Out of Plini. Wormwood helps digestion. With rue pepper and salt. It taketh away rawness of the stomach, old men of olde time gave it to purge with a pint and a half of olde sea water, six drachms of seed. iii. of salt with two once of honey and. ii. drachms in the jaundice it is drunken with raw parsley or Venus’s hair. It is good for the clearness of the sight, it heled fresh wounds before there come any water in them. Laid among clothes it drives the moths away. The smoke of it drives away gnats or midges. If the ink be tempered with this juice it maketh the mouse they will not eat the paper, that is written with that ink. The ashes of it with rose ointment maketh black hair. The quantity out of Mesue. Ye may take of the broth or of the stepping of wormwood from v. once to viii. of the juice, from the drachms to. iiii. of the powder from ii. drachms tot iii. and so will it make a purgation. But because it worketh but weekly, by itself ye may take it with whey, with Raisins. the stones taken out, or with roses or fumitory. Sea Wormwood is not to be used for the right Wormwood, for it is noisome unto the stomach, as Dioscorides and Gale do testify. Nether is the common Wormwood to be taken for the right, if it may be had. |

|

Of Sothernwod. Sothernwode is called in Greke, Abroton, in Latin Abrotonum, in duche Affruish or stabwurtz, in frenche Anronne. Dioscorides maketh two kindes of Sothernwode, the one kynde is the male, it growth in gardynes, and no where els, this is our comen Sothernwode. The other kynde is the female, and diverse learned men have supposed the herbe, called in Englisch lavander cotton to be thys kind, and surelye the description doth much agree, savynge; that the leaves of lavender cotton are not lyke unto sea wormwode, for it hath much thinner and fyner leves then lavender cotton hath. This kynde of Sothernwode, wherof I intreat now, is called of Dioscorides in the description of sea Wormwode, Abrotonum parvum. Wherefore I am fully persuades that a certain kind of Sothernwod which growth in the mountaynes of Italye, is the right Sothernwode female. It hath small leaves and short, but very thyck together, and it hath the very same smell that the other kynde hath. Sothernwode is hote and drye in the third degree. The vertues. The sede of Sothernwode, rawe, broken, made hote in water and so drunken, is good for the short wynded, for the partes that are drawen together or stronke, and are bursten, for the sciatica, for the stopping of the water, likewise of wemens floures. The same drunken with wyne is a good preservative against poyson. It is good for them that shake and shudder for colde, sodden in oyle, and layd to upon the body. This herbe both strowene in the bedde, and also with the smoke that commeth from it, driveth serpentes away. It is good for the inflammation of the eye layd with a sodden quince or with breade. The same broken with barley mele and jodene, driveth awaye swellynges on the fleshe. It kylleth wormes, for it is bytter. Sothernwode burned and put in the oyle of Palma christi or radyce maketh a berde and growth slowlye, come oute a pace, if it be anointed with it. Sothernwode draweth oute it that stycketh fast in a mannys body. Some holde that thys herbe layd but under a mannys bolster, provoketh men to the multyplyenge of their kynde, and that it is good agaynst chermynge and wychyng of men, which by chermynge are not able to excersise the worke of generacion. |

Of southernwood. Southernwood is called in Greek, (Artemisia abrotanum), in Latin Abrotanum, in German Affruish or stabwurtz, in French Auronne. Dioscorides maketh two kinds of southernwood, the one kind is the male, it growth in gardens, and nowhere else, this is our common southernwood. The other kind is the female, and diverse learned men have supposed the herb, called in Englisch lavender cotton to be this kind, and surely the description doth much agree, saving; that the leaves of lavender cotton are not like unto sea wormwood, for it hath much thinner and finer leaves then lavender cotton hath. This kind of southernwood, whereof I intreat now, is called of Dioscorides in the description of sea Wormwood, Abrotonum parvum. Wherefore I am fully persuading that a certain kind of southernwood which growth in the mountains of Italy, is the right southernwood female. It hath small leaves and short, but very thick together, and it hath the very same smell that the other kind hath. southernwood is hot and dry in the third degree. The virtues. The seed of southernwood, raw, broken, made hot in water and so drunken, is good for the short winded, for the partes that are drawn together or shrunken, and are bursting, for the sciatica, for the stopping of the water, likewise of women’s flowers. The same drunken with wine is a good preservative against poison. It is good for them that shake and shudder for cold, sodden in oil, and laid to upon the body. This herb both strewn in the bed and also with the smoke that comet from it drive serpents away. It is good for the inflammation of the eye laid with a sodden quince or with bread. The same broken with barley mele and iodine, drive away swellings on the flesh. It killed worms, for it is bitter. southernwood burned and put in the oil of Palma christi or radish maketh a hard and growth slowly, come out a pace, if it be anointed with it. Southernwood draweth out it that sticked fast in a man’s body. Some hold that this herb laid but under a man’s bolster, provoked men to the multiplying of their kind, and that it is good against charming and witching of men, which by charming are not able to exercise the work of generation. |

|

Acanthium. Acanthium is a kynde of thystel indented after the fashion of branke ursin, but the grappes are not so far in sunder, the lefe broken hath in it a longe thing lyke cotton or fyne doune, the heade is lyke the head of a tasell, but muche lesse, It hath blewe floures, the hole herbe is clammy, and hath a stronge savoure. I never sawe it growe, but in gardynes in England and in Italy, some say that the Herbaries name it Carduum asinum, but as yet I coulde never learne any Englysh name of it, I for a fhyst therefore am compelled to name it Ote thystelle or cotton thystell, because the sedes of the herbe are lyke Otes and te leve broken resemble cotton. The vertues of the thystell. I fynde no other good propertye, that Dioscorides sayeth, that thys Herbe hath, saving that it is good for them that have their neks bowing backward by violence of a crampy disease, but not of nature. It groweth in Londen in Doctor Barthlettis gardin. |

Acanthium. (Acanthium spinosum of mollis) Acanthium is a kind of thistle indented after the fashion of brank ursin, but the grapes are not so far in sunder, the leaf broken hath in it a long thing like cotton or fine dons, the head is like the head of a teasel, but much lesser. It hath blue flowers, the hole herb is clammy, and hath a strong savor. I never saw it grow, but in gardens in England and in Italy, some say that the Herbarizes name it Carduus asina, but as yet I could never learn any English name of it, I for the first therefore am compelled to name it Ot thistle or cotton thistle, because the seeds of the herb are like Ote (oat?) and the leaf broken resemble cotton. The virtues of the thistle. I find no other good property, that Dioscorides sayeth, that this herb hath, saving that it is good for them that have their neks bowing backward by violence of a crampy disease, but not of nature. It growth in Londen in Doctor Barthlettis Garden. |

|

Of brank Ursyne. Acanthus is called of barbarus wryters branca Ursina, in English branke Ursyne, in duche bernklauw. This herbe growth plentuously in my lords gardyne at Syon. I never sawe it growe wylde as yet. Some have abused bearfoot, whiche is consiligo for this herbe, but the descriptyon of Dioscorides condempneth them. True branke ursyne hath leves lyke a certayne kind of cole, whose leves are intented, but the leves are blacker, green, and muche longer then cole leves are, and also narrower and more depe cut in, towarde the synowe that goeth thorow the myd lefe. The hole herbe is very sleymy and full of a sleperynuce. They that wyll have anye more of the description of branke ursyne, let them rede Dioscorides de Acantho. The vertues. Branke ursynes rote is good for members out of ioynte and for burnynge, if it be layd upon the diseased places. The same drunken provoketh uryne, but it stoppeth the bellye, it is wonderfull good for burstynges and places drawen together, and for them that have the prysike or consumption. Plini sayth also that this herbe is good for the gowt, warmed ad layd to the place, whiche is vexed with it. |

Of brank Ursine. (Heracleum sphondylium) Acanthus is called of barbarous writers branca Ursina, in English branke Ursine, in German bernklauw. This herb growth plenteously in my lord’s garden at Syon. I never saw it grow wild as, yet. Some have abused bearfoot, which is consiligo for this herb, but the description of Dioscorides condemned them. True branke ursine hath leaves like a certain kind of Cole, whose leaves are indented, but the leaves are blacker, green, and much longer than Cole leaves are, and also narrower and deeper cut in, toward the sinew that goth thorough the mid leaf. The hole herb is very slimy and full of a slippery juice. They that will have any more of the description of branke ursine let them rede Dioscorides de Acantho. The virtues. Brank ursine’ s root is good for members out of joint and for burning, if it be laid upon the diseased places. The same drunken provoked urine, but it stopped the belly, it is wonderful, good for bursting’s and places drawn together, and for them that have the physique or consumption. Plini say also that this herb is good for the gout, warmed ad laid to the place, which is vexed with it. |

|

Aconitum. Aconitum is of. ii.sortes in Dioscorides, the first is called Pardalianches, or thelyphonum or theiophonum. This kind hath leves lyke concummers or sowes bred iii. or iiii. together, the root resembleth a scorpions tayle, and shyneth lyke alabaster, Fuchsius with diverse other learned men have thought that the herbe, whyche the duche men call einbere is Aconitum Pardalianches, but I doubt whether it be so or no, for the herbe hath ever iiii. Leves lyke plantain, without any roughnes and never hath, iii. leves. More over over I have heard of credyble persones, that chyldren in some places eat the black berrie, that growth in the top of this herbe without any leopardy, which they could not do, if this herbe were Pardalianches, which may well be called in Englisch lyberdes bayne. The herbe that hath bene taken for lyberdes bayne, growth plantivully beside Morpeth in Northumberland in a wod called cottyngwod. The other kynde of Aconitum is devided of Dioscorides into iii. sortes, of which I know .ii. kyndes, one of them hath leves lyke a plain tre, and deeply ententyd with yellow flowres, and with lyttle short coddes with black sedes in them, this kynde growth onlye in gardynes, as farr as I knowe; and this maye be called wolfes bayne, or yelowe wolfes bayne, or plain wolfes bayne. The other kind hath leves lyke a great kynde of Crowfont with a lang stalke and a blew floure in the top of it, lyke a hode, such as graye fryers were. Wherefore the lower Germanes call it monickes cap or munch cappen, that is monkes hod. This kynde growth very plentuously in the very top of the alpes, between spleunge and clavenna. The propertyes. Leopardes bayne layd to a scorpione maketh hyr utterly amased and Num, and assone as she toucheth agayne Hellebor, or nesewurt, she commeth to her selde again, some use this herbe, layng it unto the eyes to take away the great paines of the eyes, this herbe hyd in fleshe and casten furth, where wylde beastes come, kylleth as many eat it. The other kyndes called wolfes bayne, and monkes coule kylleth wolves. And this wolfbayne of all poysones is the most hastye poison. Howbeit, Plini saith, that this herbe is good to be drunken against the byting of a scorpyone. Thys is also the nature of wolfes bayne if anye credence maye be given unto Plini, that it will kyll a man if he take it, except it fynde in a man, some thynge it may kyll, with that it wyll stryve as with hys muche, which it hath founde within the man. But this fyghtyng is only, when is hath founde poison in th bowelles of a lyuyng creature. And marveyl it is, tht two dedly poysones do both dye in a man that the man may lyve. Remedies against this poison and tokens of it, wherby it may be knowen who is poysonet with it. Wolfis bayne by and assone as it is in drynkynge apereth in the tonge swete with a certain byndyng, and when they that have taken it, begyn to rise, it maketh them dosey in the heade, and dryveth out teares, and bryngeth great heuynes unto the breste and mydrysse and much wynd goeth furth. Wherefore the poison must be driven owt, ether with vomiting, or els beneth, wyth a clyster. We use to gyve in drynke, organe, rue, horehounde, or the broth of Wormwode with wormwode wyne, or with houseleek, or sothernwode, or grounde pyne. The cruddes found in a kyddes maw, or an hyndecalfes maw, or a leverettis cruddes with vinegre, are good for the same. Germanders, bevers coddes aris and rue, do properly pertayne to the healyng of this poison. |

Aconitum. Aconitum is of. ii. sorts in Dioscorides, the first is called (Doronicum pardalianches) Pardalianches, or thelyphonum or theirophonum. This kind hath leaves like consumers or sows bred. iii. or. iii. together, the root resembled a scorpion’s tail and shineth like alabaster, Fuchsius with diverse other learned men have thought that the herb which the German men call einbere (Paris quadrifolia) is Aconitum Pardalianches, but I doubt whether it be so or no, for the herb hath ever iiii. leaves like plantain, without any roughness and never hath, iii. leaves. Moreover, I have heard of credible persons that children in some places eat the black berry, that growth in the top of this herb without any Leopardi, which they could not do if this herb were Pardalianches, which may well be called in Englisch leopards’ bane. The herb that hath bene taken for leopards’ bane, growth plentifully beside Morpeth in Northumberland in a wood called cottonwood. The other kind of Aconitum is divided of Dioscorides into iii. sorts of which I know. ii. kinds, one of them hath leaves like a plain tree, and deeply intended with yellow flours and with little, short pods with black seeds in them, this kind growth only in gardens, as far as I know; and this may be called wolfs bane or yellow wolfs bane or plain wolfs bane. The other kind hath leaves like a great kind of Crowfoot with a lang stalk and a blue flower in the top of it, like a hoed, such as gray fryers were. (Aconitum napellus) Wherefore the lower Germans call it monickes cap or munch cappen, that is monks hod. This kind growth very plenteously in the very top of the Alpes, between Spleunge and Clavenna. The properties. Leopards’ bane laid to a scorpion maketh hire utterly amazed and Num, and as soon as she touched agene Helleborus or sneezewort she comet to herself again, some use this herb, laying it unto the eyes to take away the great pains of the eyes, this herb hid in flesh and caste furth, where wild beasts come, killed as many eat it. The other kinds called wolfs bane, and monks cover killed wolves. And this wolfbane of all poisons is the most haste poison. Howbeit, Plini saith, that this herb is good to be drunken against the biting of a scorpion. This is also the nature of wolfs bane if any credence may be given unto Plini, that it will kill a man if he takes it, except it find in a man, something it may kill, with that it will strive as with his much which it hath found within the man. But this fighting is only, when is hath found poison in the bowels of a living creature. And marvel it is, that two deadly poisons do both dye in a man that the man may live. Remedies against this poison and tokens of it, whereby it may be known who is poisoned with it. Wolfis bane by and as soon as it is in drinking appear in the tong sweet with a certain binding, and when they that have taken it, begin to rise, it maketh them dosed in the head and drive out tears, and brength great heaviness unto the breast and midriff and much wind goth furth. Wherefore the poison must be driven out, ether with vomiting, or else beneath, with a clyster. We used to gyve in drink, origan, rue, horehound or the broth of wormwood with wormwood wine, or with houseleek or southernwood, or ground pine. The crudes found in a kidder’s maw, or a hind calves’ maw, or a leveret’s crudes with vinegar are good for the same. Germanders, bevers pods arise and rue do properly pertain to the healing of this poison. |

|

Of Acorus. There hath bene longe a great error amonge the Phisycianes and Apothecaryes in thys herbe Acorus, for the have used for the true Acorus, an herbe in dede lyke in fashion unto Acorus, but in qualyte so farre differynge, as one herbe allmoste maye dyffer from another. Acorus is hote in the thyrde degre and glad on, whyche they use for Acorus is could and wonderfully stoppynge an astringent. Amonge the learned men, whyche have percevyd the foresaid error, is some stryfe for this herbe, some holdyng that the comen calamus odoratus is the true Acorus, and other some affirming that great galanga is the true Acorus. Calamus aromaticus is very bytter, and in the smell hath a certain unpleasantness that filleth the head, and the hete in this herbe is not so great as Dioscorides requireth, for Dioscorides sayth that the roote of Acorus is sharpe or bytynge, and hath noth an evell savour. Then when as the greater, Galanga is hote in the third degree, and without any great bitterness and evell savoure. I would rather take great Galanga for acorus, then the comon calamus. The vertues. Acorus hath an hote tote, the brothe of it provoketh urine. It is good for the paynes of the syde of the lyver of the breste, gnawing in the guttes, drawings together and burstynges, it is good to sytt over for wemens diseases, als arisis. It wasteth away the mylt, and helpeth the strangulion and the byting of serpentes. It driveth away the darknes of the eyes with the iuice. The broth of this herbe is also good for the swellyng of the stones, if it be soden in wyne, als layd to, after the same maner is it good for hardnes and gathering to gether of humores. A scruple of this tot dronkene with, iiii. unces of honeyed wyne, is good for them that have be brused and overthrown. Acorus is hote and dry in the third degre. |

Of Acorus. (Acorus calamus) There hath bene long a great error among the Physicians and Apothecaries in this herb Acorus, for the have used for the true Acorus, an herb indeed like in fashion unto Acorus, but in quality so far differing, as one herb almost may differ from another. Acorus is hot in the third degree and glad on, which they use for Acorus is could and wonderfully stopping an astringent. Among the learned men which have perceived the foresaid error, is some strife for this herb, some holding that the conmen Calamus odoratus is the true Acorus, and other some affirming that great galanga is the true Acorus. Calamus aromaticus is very bitter and in the smell hath a certain unpleasantness that fill the head, and the hot in this herb is not so great as Dioscorides required, for Dioscorides say that the root of Acorus is sharp or biting, and hath not an evil savor. Then when as the greater, Galanga is hot in the third degree, and without any great bitterness and evil savor. I would rather take great Galanga for Acorus, then the common calamus. The virtues. Acorus hath an hot tote, the broth of it provoked urine. It is good for the pains of the side of the liver of the breast, gnawing in the gutters, drawings together and bursting’s, it is good to sit over for women’s diseases, as rises. It wasted away the milt and helped the strangling and the biting of serpents. It drives away the darkness of the eyes with the juice. The broth of this herb is also good for the swelling of the stones, if it be sodden in wine and laid to, after the same manner is it good for hardness and gathering to gather of humors. A scruple of this tot drunken with, iiii. once’s of honeyed wine, is good for them that have be bruised and overthrown. Acorus is hot and dry in the third degree. |

|

Of Venus heyre. Adianthus is called in duche Jungfrawen haar, and in the Pothecaries shoppes, capillus veneris. May erroures have ben about this herbe. I have sene some Pothecaries in Antwerpe use for thys herbe Dryopteris, in louan other use walle rue, otherwise called salvia vite, for this herbe. And our Pothecaries of Englande use Trichomanes, whiche they calle maydens heyre, for Adianto. Whose error is sownest to be for geven for trichomanes and Adiantum are, as Dioscorides sayth, of lyke virtue. Nevertherles the error remanath for Adiantum hath many lytle branches commynge furth of a lytle stalke, with leves lyke coriandres greater leves, and this herbe resembleth even so the brake, as trichomanes resembleth the male brake, for trichomanes vnen from the roote hath continually leves unto the top, as the male brake hath, and Adiantum bare a goo waye above the roote, as the she ferne is bare even to top, there is is fulle of leves. I have sene this herbe diverse tymes in Italye, in pyttes and welles; but I could never fynde it, neither in Germany, nor in England. It useth to growe also in watery rockes, wheras the sunne commeth lyttle, it may be named in English Venus heyre or ladyes heyre. The vertues. The broth of Venus heyre drunken, is good for the short wynded, and for them that syghe much, for the mylt, for the yellow iawndes, for them that cannot well make water. It breaketh the stone, it stoppeth the fluxe of the belly, it remedieth the bytynges of serpentes. It is good to drynke against the flyxe of the stomacke. It draweth doune the seconds and the floures of wymen, and stoppeth the parbrekynge and spyttyng of bloude. The herbe rawe is good for the bytyng of serpentes, layd unto the place bytten. It maketh thycke heyre, wher as the scales have taken is waye, it dryveth awaye wennes and swellyng under the chyn and in other places and with lye it taketh awaye scurfe and scales of the heade, and health the wareryng sores of the same. It holdeth on the heyre, that wolf fall of, if Ladanum be mixed with it, and layd upon the heade with myrt oyle, lyly oyle or with ysope and wyne. Thys herbe given in, in meat unto quales and cokkes maket them feyght more earnestly, then they dyd before. Thys herbe bryngeth furth of the breste toughe and thycke humores. Venus heyre is in mean temper between hote and colde. Mesue wryteth, that the broth where in is soden a pound of thys herbe beynge grene, purgeth yellow choler, and draweth furth fleme out of the hole belly, and lyver, and bryngeth furth of the breste and lunges by spyttyng, tough and clammy humores. |

Of Venus hair. (Adiantum capillus-veneris) Adiantum is called in German Jungfrawen haar, and in the Pothecaries shoppes, capillus-veneris. Many errors have been about this herb. I have seen some Pothecaries in Antwerp use for this herb Dryopteris, in Louann other use wall rue, otherwise called salvia vita, for this herb. And our Pothecaries of England use Trichomanes, which they call maidens hair for Adiantum. Whose error is soonest to be forgiven for Trichomanes and Adiantum are, as Dioscorides say of like virtue. Nevertheless the error remine for Adiantum hath many little branches coming furth of a little stalk with leaves like corianders greater leaves, and this herb resembled even so the brake, as Trichomanes resembled the male brake, for Trichomanes even from the root hath continually leaves unto the top, as the male brake hath, and Adiantum bare a go way above the root as the she fern is bare even to top, there is full of leaves. I have seen this herb diverse times in Italie, in putts and wells; but I could never find it, neither in Deutsche, nor in England. It used to grow also in watery rocks, whereas the sun comet little, it may be named in English Venus hair or ladies’ hair. The virtues. The broth of Venus hair drunken is good for the short winded and for them that sigh much, for the milt, for the yellow jaundice, for them that cannot well make water. It breaks the stone, it stopped the flux of the belly, it remedied the biting’s of serpents. It is good to drink against the flux of the stomach. It draweth dons the seconds and the flowers of women and stopped the pairbreaking and spitting of blood. The herb raw is good for the biting of serpents, laid unto the place bitten. It maketh thick hair whereas the scales have taken is away, it drives away wennes (Ichthyosis?) and swelling under the chin and in other places and with lye it taketh away scurf and scales of the head and health the warring sores of the same. It holds on the hair, that will fall off if Laudanum be mixed with it and laid upon the head with mirth oil, lily oil or with hyssop and wine, this herb given in, in meat unto quale’s and cokes make them fight more earnestly, then they did before. This herb brength furth of the breast tougher and thick humors. Venus’s hair is in mean temper between hot and cold. Mesue write that the broth where in is sodden a pound of this herb being green, purged yellow choler, and draweth furth flehm out of the hole belly, and liver, and bringeth furth of the breast and lunges by spitting, tough and clammy humors. |

|

Of the right affodyll. Albucum is called in latin also Hastula regia, and in Greke asphedelos, and it may be called in Englysh right affodill. Howbeit, I could never se thys herb in England but ones, for the herbe that the people calleth here Affodil or daffodil is a kind of narcissus. The right affodil hath a longe stalke a cubit long, and some thynge longer many whyte floures in the top, and not one alone als the kyndes of Narcissus have. Theophrastus sayth, that ther growth a worme in affodyles, and that it goweth unto a kynde of flye and fleeth out when the floure is rype. The sede is thre square like bucke wheat or beach aples, but is backer and harder, the leves are long as a great leke leves are, and the rootes are many together lyke acorns. I have sene thys herbe oft in Italye and in certayne gardines of Antwerp and now I have it in England in my gardin. The vertues. The properties. The rootes of the right affodyl are byting sharpe, and do hete and provoke uryne and wemens floures. A drame of the rotes drunken in wyne, helpe the paynes in the syde, bursten places and shrunken together, and coughes. The same taken in quantite of the under ankle bone, suche as men playe with, helpeth vomytyng if it be eaten. The drammes weight of the same is good for them thar are byten of a serpent. Ye must anoynte the bytyng with the leves, floures and rootes wyth wyne. Do so also to foule and consumpyng sores. The rootes so den in the dregges of wyne, are good for the inflammations of the papes and mennis stones, for swellynges and for byles. Is is also good for newe inflammations layd to with barley mele. The iuice of the roote soden with old swete wyne, myr and saffron, is a good medicine for the eyes. It is also good for matery eares brused mith frankincense, honeye, wyne, and myrr, the same put in the contrary ear, swageth the tuthake. The ashes of the root layd to, maketh heyr grow agayne in a skalled head. Oyle soden in the fyre in the rootes made hollow is good for the kybes, or moules that are raw, and for the burning of the fyre, poured into the ear, it is good for defenes. The roote heleth whyte spottes in the fleshe, if ye rub them first with a cloth, and afterwards lay the roote to them. The seed and the floures drunken in wyne, withstand wonderfully the poysone of scolopendres and scorpiones. They purge also the belly. |

Of the right affodil. (Asphodelus albus) Albucum is called in Latin also Hastula regia, and in Greek asphedelos, and it may be called in English right affodil. Howbeit, I could never see this herb in England but ones, for the herb that the people calleth here Affodil or daffodil is a kind of narcissus. The right affodil hath a long stalk a cubit long, and something longer many white flowers in the top, and not one alone as the kinds of Narcissus have. Theophrastus say that their growth a worm in affodil and that it growth unto a kind of fly and fleet out when the flower is ripe. The seed is three square like buckwheat or beach apples, but is backer and harder, the leaves are long as a great leek leaves are, and the roots are many together like acorns. I have seen this herb oft in Italie and in certain gardens of Antwerp and now I have it in England in my garden. The virtues. The properties. The roots of the right affodil are biting sharp and do hot and provoke urine and women’s flowers. A drachma of the rotes drunken in wine help the pains in the side, bursting places and shrunken together, and coughs. The same taken in quantity of the under-ankle bone, such as men play with, helped vomiting if it be eaten. The drachms weight of the same is good for them thar are bitten of a serpent. Ye must anointed the biting with the leaves, flowers and roots with wine. Do so also to foule and consumption sores. The roots sodden in the dredges of wine are good for the inflammations of the pappa and men’s stones, for swellings and for bile’s. It is also good for new inflammations laid to with barley mele. The juice of the root sodden with old sweet wine, myrrh and saffron is a good medicine for the eyes. It is also good for mattery for ears bruised with frankincense, honey, wine, and myrrh, the same put in the contrary ear swaged the toothache. The ashes of the root laid to, maketh hair grow again in a scaled head. Oil sodden in the fire in the roots made hollow is good for the kibbes or moules that are raw and for the burning of the fire, poured into the ear, it is good for deafness. The root health white spots in the flesh, if ye rub them first with a cloth, and afterwards lay the root to them. The seed and the flowers drunken in wine, withstand wonderfully the poisoned of Scolopendra’s and scorpions. They purge also the belly. |

|

Of Garlick. Garleke is called in Greke Skorodon, in Duche knoublouch, in Frenche Aul or aur. Ther are .iii, kyndes of Garleke. The first is the common gardin garleke, the second is called in Greke Ophioskorodon, in latyn Allium anguinum or allium sylvestre; in Englyshe crouwe garlyke or wild garlyke. Thys kynde hathe very small leves commyng furth lyke grene twigges and they are commonlye croked at the end, and when it is rype it hathe sede in de tope even lye unto the cloves which growe in the roote but they are lesse. The third kind is called allium ursinum in latin, and in Englysh rammes or ramseyes; the first kynde growe onley in gardynes in England, and the second growth in myddes and feldes in every cuntre, the thyrde kynde growth in woddes about bath. The vertues of Garlyke. Garlyke warmeth the bodye and breaketh insundre grosse humores, and cuttethe in peces toughe humores. Garlyke twyse or thryse soden in water, putteth away hys sharpnes and yet for al that it leseth not hys virtue in makynge subtyle and fyne it that is grosse. But it wynneth therby a certayne pour, though it be not easy tobe perceyued, to noryshe the body, which it had not befor it was soden. Garlyke is not onlye good meat but also goof medicine, for it can lose it that is stopped and also dryve it awaye. Garlike is of that kynde of meates whyche dryve further winde and ingendere no thirst. Crow garlyke as all other wilde herbes be, is stronger then it of the gardyne. Garlyke dryveth of the belly brode Wormes taken with other meat, it provoketh uryne, it helpeth the bytyng of a veper. Bothe eaten and also layd to, it is good against the bittinges of madd or weod beastes. It is also very good for the ieopardies that may come of changing of waters, cuntrees, it clereth the voyce, swageth the olde coughe, taken row or soden. The same droncken with the brothe of organe kylleth lyse and nyttes. The ashes of burned garleke layde to with hony helethe bruses and blewe stryppes folowinge of betynge or fallynge and with the ointment of spykenarde; it heleth the fallynge of the heere, and with oyle and salt it heleth the burstynges owt of wheles, and with hony it taketh away the scrupruye evell, frekelles, runnynge sores of the hede and schurfe and leprosyes. It is medycynable against the poysone of lybardes bayne. It draweth downe wemenes syknes and secundes with the perfume of it, and so doeth it, if they will sit over the brothe that it is so dene in with herbes of lyke softe chefe, stanceth the fallynge downe of humores called the catarre. And so ist gooed agaynste horsues. Thre lytle cloves broken in vynegre and layde to the tethe if it be rosted and putt in the tethe ake. It swagethe also the payne come of to muche moysture. One hede of garlyke dronkene with .x. drammes of the gume of laserpytyum, dryvethe away the quaertayne ague. For lake of the true laserpytyum; ye may take the roote of angelyca or pyllyrorye of spayne, called other wyse magystrantya. It pprovoketh slepe and maketh the coloure of the bodye rede, and styrresthe men to venerye, dronkene with grene Coryander and stronge wyne. It is also good for the pyppe or roupe of hennes and cockes, as Pliny wrytesh. Garleke helpethe the colyke cummeth of wynde and the sciatica that is of fleme. It maketh subtill the norystement and the bloud. The use of garleke is evell for all them are of an hote complexion, for it hurtethe the eyes, the hede, the longes, and the kydnes, it hurteth also women with child and suckyng chylder. Garleke is as Galene sayth, the men of the countress triacle. It is hote and drye in the fourth degree. |

Of Garlick. (Allium sativum, Allium ursinum) Garleke is called in Greek Skorodon, in German knoublouch, in French Aul or aur. There are. iii, kinds of Garlick. The first is the common garden Garlick, the second is called in Greek Ophioskorodon, in Latin Allium anguinum or allium sylvestre; in English crow Garlick or wild Garlick. This kind hath very small leaves coming furth like green twigs and they are commonly crooked at the end and when it is ripe it hath seed in de tope even like unto the cloves which grow in the root, but they are less. The third kind is called Allium ursinum in Latin, and in English rammes or ramseies; the first kind grow only in gardens in England, and the second growth in middles and fields in every country, the third kind growth in woods about Bath. The virtues of Garlick. Garleke warmth the body and break in sunder grosses humors and cut it in pieces tough humors. Garlick twice or thrice sodden in water, putted away his sharpness and yet for all that it lest not his virtue in making subtill and fine it that is grosses. But it wants thereby a certain power, though it be not easy to be perceived, to nourish the body, which it had not before it was sodden. Garlick is not only good meat but also goof medicine, for it can lose it that is stopped and also drive it away. Garlick is of that kind of meats which drive further wind and engendered no thirst. Crow garlic as all other wild herbs be, is stronger than it of the garden. Garlick drive of the belly brood worms taken with other meat, it provoked urine, it helped the biting of a viper. Bothe eaten and laid to it is good against the biting’s of mad or wild beasts. It is also very good for the jeopardies that may come of changing of waters, countries, it claret the voice, swaged the olde cough, taken row or sodden. The same drunken with the broth of origan killed lyse and nits. The ashes of burned Garlick laide to with honey heal the bruises and blue stripes following of biting or falling and with the ointment of spikenard; it health the falling of the hair and with oil and salt it health the bursting’s out of whiles, and with honey it taketh away the scurry evil, freckles, running sores of the head and scurf and leprosies. It is medicinable against the poisoned of leopard’s bane. It draweth down women’s sickness and secund with the perfume of it and so doeth it, if they will sit over the broth that it is so den in with herbs of like soften chose, stanch the falling down of humors called the catarrh. And so is it good against horses. Three little cloves broken in vinegar and laide to the teethe, if it be roosted and putt in the teethe ache. It swaged also the pain come off to much moisture. One head of garlic drunken with.x. drachms of the gum of Laserpitium, drivee away the quartan ague. For lake of the true Laserpitium, ye may take the root of Angelica or pellitory of Spain, called otherwise magistrantia. It provoked sleep and maketh the color of the body red and stirred men to vinery, drunken with green Coryander and strong wine. It is also good for the pipe or rope of hens and cocks as Plini write. Garlick helped the colic comet of wind and the sciatica that is of flehm. It maketh subtill the nourishment and the blood. The use of Garlick is evil for all of them are of an hot complexion, for it hurt the eyes, the head, the lunges, and the kidneys, it hurt also women with child and sucking children. Garlic is as Galene say, the men of the country’s treacle. It is hot and dry in the fourth degree. |

|

Of the alder tree. The alder tree, whiche is also called an aller tree, is named in greke Clethra, in latin alnus, in duche, ein erlenbaum. The nature of thys tree is to growe by water sydes and in marrische grounde. The properties of alders. The tree when the barke is of, is reade, and the barke is muche used to dye with all. Plini sayth, that alder is profitable to set at river sydes against the rage of the floude, to helpe and strengthem the banke with all; and that under the shadowe of alder trees, maye well growe anye thynge, that is sett, or sowen; which thing chaunceth not under many other trees. Some saye that the iuice of an alder trees barke, is good for a burning. The leves are colde and astringent, and so is the barke also. |

Of the alder tree. (Alnus glutinosa) The alder tree, which is also called an aller tree, is named in Greek Clethra, in Latin Alnus, in German, ein erlenbaum. The nature of this tree is to grow by water sides and in marris ground. The properties of alders. The tree when the bark is of is red and the bark is much used to dye with all. Plini say that alder is profitable to set at river sides against the rage of the flood, to help and strengthen the bank with all; and that under the shadow of alder trees may well grow anything that is set or sown; which thing chanced not under many other trees. Some say that the juice of an alder tree’s bark is good for a burning. The leaves are cold and astringent and so is the bark also. |

|

Of Aloe. Aloe maye be called in Englysch herbe Aloe to put difference between the herbe and the iuice which compacted together and dryed into great peces is commonly called aloe. Aloe hath fat and thycke leves lyke unto squilla or sea oinyone, somthyng brode, round and bewynge bachwarde. It hath leves of eche syde, growynge a wrie, pryckye, with few crested and short. The stalke is lyke right affodilles stalke, it hath whyte floures, and fruyte like unto right affodyl, it hath a grievous savour and a wonderfull bytter taste. It hath one roote, and stycketg in the grounde lyke a stake. I have sene in Italye in diverse gardynes herbe aloe, but it endureth not in Italye in gardynes, above iii. Yeares; as Italianes tolde me. I have sene herbe aloe also in Antwerpe in shoppes, ther it endureth longe alive, als orpine doth and housleke, wherefore some have called it semper vivum marinum, that is sea aigrene. The vertues. There are two kyndes of aloe, one kynde is full of sande, semeth to be the drosse and out cast of the pure iuice. The other kynde is like unto a lyver, that ought to be taken, that is of a goof favoure pure, and hathno deceyt in it, shynynge without stones, of a read colour, growing together lyke a lyver, brittle, easy to melt and of a great bitternes. It thath is black and hard to breake is not commendyd. Th nature of the herbe Aloe is to hele woundes and the property op the iuice is to drye up, to provoke slepe and to make bodies thicke and fast together, and to louse the belly, two lytle spunfulles of aloe beat into puoder, and taken ether with colde or with warme water purgeth the stomake, stoppeth the vomytyng of bloude, and purgeth the iawndess, taken in the quantyte of a scruple and a halfe with water or a drame in drynke, thre drames of Aloe taken, make a iust purgation. Mesue gyveth in pouder or pylles from a drame and a halfe to two drammes, and instepe or infuse from an drame and a halfe unti iii. drammes and a halfe. Aloe mixed with other purgations helpteh and they hurt not the stomake so much as they wold have done if they had bene taken alone. Aloe dried, is sprinkled into woundes to make them growe together agayne. It bringeth sores to a skyne, holdeth them in, that they sprede no farther. It heleth specially the pryvy member that have sores and the skyne of. It iopenth together agayne the skyne that covereth the knope of boyes yeardes, if it be broken in sunder with Malvesy. It heleth rystes and hard lumpes, aryse in the fundament. It stoppeth over much isshuyng of emrodes, burstyng out of bloud. It heleth also agnales, when they are cut of. With hony it taketh awaye blewe markes and tokens that come of bearing or brusyng. It heleth scabie blere eyes, in the niche of the cornes of an eye. It stancheth the heade ake, layd unto the temple of the forehead with vinegre ad rose oyle, with wyne layd unto the heade. It holdeth fast the heere that wold fall of. It is good for the swellyng in the kirnelles under the tonge for the disease of the goumes and al other disease of the mouth layd with with wyne and hony. Aloe is burnt in a clene and burning hote vessel, and is oft stirred with a fether, that I may be all alyke rosted, and so it is good medycyne for sore eyes. Some tyme it is washed, that the sande may go unto the bottome. Aloe washed, is holsummer for the stomake, but it purgeth not so much as unwashed. Aloe purgeth choler and fleme. It purgeth souner asl Mesue sayeth if it be taken before meate, and if therbe menged with it mace, clowes nut mugges cumanum, masticke or folsot. Wyne or rose water, or the iuice of fenell, wherein Aloe mixed with dragonis bloud, and myrr health stynkynge and olde sores. The same mixed wyth mirr, kepeth dead bodyes from corruption. Aloe dissolves with the whyte of an egge, is a good unplaster tot stop bloud, both that are much disposes to the emrodes, for it openeth the mouthes of the vaynes. It is also evell for them thar are hote and drye of nature, but it is good for them thar are moyst and cold. Aloe is hote in the begynnynge of the second degree, and dry in the third degree. The best aloe as Galene writeth commeth from Indy. |

Of Aloe. Aloe may be called in English herb Aloe to put difference between the herb and the juice which compacted together and dried into great pieces is commonly called aloe. Aloe hath fat and thick leaves like unto squilla or sea onion, something brood, round and bowing beachward. It hath leaves of each side, growing a wire, prickle, with few crested and short. The stalk is like right affodil stalk, it hath white flowers, and fruit like unto right affodil, it hath a grievous savor and a wonderful bitter taste. It hath one root and sticked in the ground like a stake. I have seen in Italie in diverse gardens herb Aloe, but it endured not in Italie in gardens, above iii. years as Italians told me. I have seen herb Aloe also in Antwerp in shoppes, there it endured long alive, as orpine doth and houseleek, wherefore some have called it sempervivum marinum, that is sea green. The virtues. There are two kinds of aloe, one kind is full of sand, seem to be the dross and out cast of the pure juice. The other kind is like unto a liver, that ought to be taken, that is of a good favor pure, and hath no deceit in it, shining without stones, of a read color, growing together like a liver, brittle, easy to melt and of a great bitterness. It that is black and hard to break is not commended. The nature of the herb Aloe is to hele wounds and the property op the juice is to dry up, to provoke sleep and to make bodies thick and fast together and to louse the belly, two little spoonful’s of aloe beat into powder and taken ether with cold or with warm water purged the stomach, stopped the vomiting of blood, and purged the jaundices, taken in the quantity of a scruple and a half with water or a drachm in drink, three drachm of Aloe taken, make a just purgation. Mesue give in powder or pills from a drachm and a half to two drachms, and instep or infuse from a drachm and a half until iii. drachms and a half. Aloe mixed with other purgation’s help, and they hurt not the stomach so much as they would have done if they had bene taken alone. Aloe dried, is sprinkled into wounds to make them grow together again. It bringeth sores to a skin, hold them in that they spread no farther. It health specially the privy member that have sores and the skin of. It open together again the skin that covered the knop of boy’s beards, if it be broken in sunder with Malvasia. It health rises and hard lumps, arise in the fundament. It stopped over much issuing of hemorrhoids, bursting out of blood. It health also ag nails, when they are cut off. With honey it taketh away blue marks and tokens that come of bearing or bruising. It health scabies blare eyes, in the niche of the corners of an eye. It stanched the headache, laid unto the temple of the forehead with vinegar and rose oil, with wine laid unto the head. It holds fast the hair that would fall of. It is good for the swelling in the kernelless under the tong for the disease of the gums and all other disease of the mouth laid with wine and honey. Aloe is burnt in a clay and burning hot vessel and is oft stirred with a feather, that I may be alike roosted and so it is good medicine for sore eyes. Some time it is washed that the sand may go unto the bottom. Aloe washed, is wholesome for the stomach, but it purged not so much as unwashed. Aloe purged choler and flehm. It purged sooner as Mesue sayeth if it be taken before meat and if the herb menged with its mace, cloves nut, muggers Cuminum, mastic or folfoote, (Arum), wine or rose water, or the juice of fennel, wherein Aloe mixed with dragons’ blood and myrrh health stinking and olde sores. The same mixed with myrrh kept dead bodies from corruption. Aloe dissolves with the white of an egg is a good unplaster to stop blood, both that are much disposes to the hemorrhoids, for it open the mouths of the veins. It is also evil for them thar are hot and dry of nature, but it is good for them thar are moist and cold. Aloe is hot in the beginning of the second degree, and dry in the third degree. The best aloe as Galene write comet from Indy. |

|

Of Chikewede. Chikewede is called in greke alsine, and the latines use the same name, in duchte vogelcraut, or mere, in frenche mauron. The Pothecaries call it, morsum galline; this herbe is so well knowen in all countrees, that I need not largelye tot describe it. They that kepe lyttle byrdes in cages, when thee are sycke, gyve the byrdes of thys herbe, to restore them to their health agayne. The vertues of Chiwede. The poure of this herbe is to bynde and to coule. It is layd to the inflammations of the eyes with barley mele and water. The iuice is also poured into the eares agaynst the payne of them. This herbe is profitable for all thing that parietory is goof for. It is good for all gatherynge and inflammatyons both of bloude and also of choler, if it be not extremely hote. |

Of Chickweed. (Stellaria media) Chickweed is called in Greek alsine, and the Latine use the same name, in German vogelcraut, or mere, in French mauron. The Pothecaries call it, morsum galline; this herb is so well known in all countries that I need not largely to describe it. They that keep little birds in cages, when they are sick, give the birds of this herb, to restore them to their health again. The virtues of Chickweed. The power of this herb is to bind and to cool. It is laid to the inflammations of the eyes with barley mele and water. The juice is also poured into the ears against the pain of them. This herb is profitable for all thing that Parietaria is goof for. It is good for all gathering and inflammations both of blood and also of choler, if it be not extremely hot. |

|

Of Henbayne. Henbayne is called in latin altercum, and Apolllinaris or faba suille in Barbarus latin iusquiamus, in greke Hyosciamos, in duche bilsem crout, in frenche de la Hanbane. Henbane hath thicke stalkes, brode leves and longe, devyded, black, and rough. The floures come out of the syde of the stalke in ordre, as the flour of pomegranates, compassed with the lytle cuppes fulle of sede as poppy hath. Ther are thre sorte of Henbayne, one with blacke sede with floures, almost purple with the leves of frenche beanes, called smilax, with veselles harde and pryckye. The other sede is something yelowe als wynter cresses is, the leves and the coddes are more simple. Both these two kyndes make men madde, and fall into a great slepe, and therefore they ought not to be commonly used. Phisicianes have receyved the thyrde kynde as most gentle full of hore, and softe, with whyte floures and whit sedes, and it growth about the sea syde, and about guttues and ditches, about townes and cytyes, which if ye cannot fynde, take the it with the reade sede and use it. The vertues. It hath the black sede is the worst kind, is not approved. A certaine iuice is pressed in the sun out of a freshe sede stalkes and leves brused, when as the moisture is dryed up, use of it, dureth for a yeare, it falleth easely into daunger of corruption. The iuice is aldo drawen out of the drye sede, brused by it selfe, laid in warme water, and then pressed out. The iuice that is pressed out, is better, releseth the paine soner then it with the milky humour, that commeth out of the herbe, by scotching or nyckyng. The grene herbe brused and mixed with wheat mele of thre monethes is made into rounde lytle cakes, and so laid up. The first iuice, that which is drawen out of the drye sede are conveniently, put in medicines, which swage payne, and they are good against quyke and hote issues, the paynes of the eares, the diseases of the mouther whit wheat mele of the fete, of other partes. The sede can do the same. It is good for the cough, for catarres, runninges of the eyes and other aykes. The same with poppy sede, about a waight of .x. graynes is drunken with mede against the excesse of wemenes syckenes and any other isshue of bloude that bursteth out. It helpeth the gowt and a mannes stones when they are swelled with wynd, sore pappes, whyche are after a womannes byrth, puffed up, do swell, if it be broken, and layd to with wyne. They use also to be put in other playsters which are ordeyned to swage payne. The leves are very good to be put in al medicynes, which take payn away both by themselves and also with barly mele. The grene leves are layd to, tot release all kynd of payne. Iii. or iiii .leves drunken with wyne hele cold agues, where in they are syck are both hote ad cold at one time. The rootes soden in vinegre as for the tuthake. The smoke of thys herbe is good for the cough, if it be received into the mouth. Plini sayth that the oyle made of the sede of thys herbe, put into a mannes eare, bryngeth hym owt of hys mynd. Also mothen .iiii .of the leves drunken, do the same. Henbayne is cooled in the thyrd degre. |

Of Henbane. (Hyoscyamus niger) Henbane is called in Latin altercum and Apolllinaris or faba suille in Barbarous Latin iusquiamus, in Greek Hyosciamos, in German bilsem crout, in French de la Hanbane. Henbane hath thick stalks, brood leaves and long, divided, black, and rough. The flowers come out of the side of the stalk in order as the flour of pomegranates, compassed with the little cups full of seed as poppy hath. there are three sorts of Henbane, one with black seed and with flowers, almost purple with the leaves of French beans, called Smilax, with vessels hard and prickle. The other seed is something yellow as winter cresses is, the leaves and the pods are simpler. Both these two kinds make men mad and fall into a great sleep, and therefore they ought not to be commonly used. Physicians have received the third kind as most gentle full of hair and soft, with white flowers (Hyoscyamus albus) and whit seeds, and it growth about the seaside, and about gutters and ditches, about towns and cities, which if ye cannot find, take it with the read seed and use it. The virtues. It hath the black seed is the worst kind, is not approved. A certain juice is pressed in the sun out of a fresh seed stalks and leaves bruised, when as the moisture is dried up use of it, dearth for a year, it falleth easily into danger of corruption. The juice is also drawn out of the dry seed, bruised by itself, laid in warm water and then pressed out. The juice that is pressed out is better, realest the pain sooner then it with the milky humor, that comet out of the herb, by scotching or nicking. The green herb bruised and mixed with wheat mele of three months is made into round little cakes and so laid up. The first juice, that which is drawn out of the dry seed are conveniently, put in medicines, which swage pain, and they are good against quick and hot issues, the pains of the ears, the diseases of the mouther whit wheat mele of the fat of other partes. The seed can do the same. It is good for the cough, for catarrhs, running’s of the eyes and other aches. The same with poppy seed, about a weight of. x. grains is drunken with Mede against the excess of women’s sickness and any other issue of blood that burst out. It helped the gout and a man’s stones when they are swelled with wind, sore pappa, which are after a woman’s birth, puffed up, do swell, if it be broken, and laid to with wine. They use also to be put in other plasters which are ordered to swage pain. The leaves are very good to be put in al medicines which take pain away both by themselves and also with barley mele. The green leaves are laid to, tot release all kind of pain. iii. or iiii. leaves drunken with wine hele cold agues, where in they are sick are both hot and cold at one time. The roots sodden in vinegar as for the toothache. The smoke of this herb is good for the cough, if it be received into the mouth. Plini say that the oil made of the seed of this herb, put into a man’s ear bring him out of his mind. Also, moth men. iiii .of the leaves drunken do the same. Henbane is cooled in the third degree. |

|

Of marrishe Mallowe. Althaea is called also Hibiscus and Eniscus and of the potecaryes malva bis malva and malvaviscus, in Englysch marysh mallow or water mallow, in duche ibish, in frenche guimauves. This herbe growth naturally in watery, marrisch myddoes, and by water sydes. Althaea or marrische mallow hath roundel eves lyke unto sowbread, whit a whit downe upon them, with a floure after the proportion of a rose, but in coloure they are pale purple, which drawyng nere unto white, for the quantite of the herbe very smalle, with a stalke of .ii. cubites high, with clammy rootes, and whyte within. It is called marisshe mallowe in Englishe, because it growth comonly in marrych ground and watery myddoes. By thys description it is playne that our comon holyoke is not Althaea. The vertues. Marrysh mallowe, soden in wyne or mede, or brused and laid on by it selfe, is good for woundes, for hard kyrnelles, swellynges, and wennes, for the burning impostume of the pappes, for the brusynge of the fundament, for wyndy swellynges, for the styfnes of the synnowes for it dryveth away, maketh rype or digesteth, bursteth, and covereth with skyne. Sett is as mencyoned before, ansdput swynes grese unto it, or goose grese, or turpentyne, that it may be clammy as an implaster, and then it is good for the inflammations and stoppynges of the mother, if ye put it into the mother after a suppostorye wyse. The brothe that the herbe is soden in, is good for the same. It draweth out also the burdens of the mother, the secundes that abyde after the child. The brothe of the roote drunken with wyne, helpeth they cannot well make water, the rawnes of them, they have the stone, blody flyxe, the sciatica, the trymblyng of any membre, the burstyngen. Washe the mouth with the same herbes soden in vinegre, it will ease the payne of the tethe. The grene sede and drye also broken, heleth frekelles and foule spottes, when they be anoynted therwith in the sunn. They that are anointed with the same, with oyle and vinegre are inno danger to be bitten of venomous beastes. It is good against the blody flixe, vomiting of bloud, the common flyxe. The same sede sodene in water and vynegre or in wyne, is drunken against all the styngyng of bees waspes and such other lyke. The leves with a lytle oyle are layd on bytynges and burnynges. It is evidently knowen that water wyll were thycke, if this rote be brused and put in, so that water stand abrode in the ayre wythout the dores. |

Of marris Mallow. (Althaea officinalis) Althaea is called also Hibiscus and Eniscus and of the pothecaries Malva bismalva and malvaviscus, in English marshmallow or water mallow, in German ibish, in French guimauves. This herb growth naturally in watery, marris meadows and by water sides. Althaea or marris mallow hath round leaves like unto sowbread, whit a whit dons upon them, with a flower after the proportion of a rose, but in color they are pale purple, which drawing near unto white, for the quantity of the herb very small, with a stalk of. ii. cubits high, with clammy roots and white within. It is called marris mallow in English because it growth commonly in marris ground and watery meadows. By this description it is plane that our common Holyoke is not Althaea. The virtues. Marris mallows sodden in wine or Mede or bruised and laid on by itself is good for wounds, for hard kernelless, swellings, and wennes (Ichthyosis?), for the burning impostume (pus) of the pappa, for the bruising of the fundament, for windy swellings, for the stiffness of the sinews for it drive away, maketh ripe or digested, burst and covered with skin. Sett is as mentioned before and put it in swine’s grease unto it or goose grease or turpentine, that it may be clammy as an plaster and then it is good for the inflammations and stoppings of the mother, if ye put it into the mother after a suppository wise. The broth that the herb is sodden in is good for the same. It draweth out also the burdens of the mother, the second that abide after the child. The broth of the root drunken with wine helped they cannot well make water, the rawness of them, they have the stone, bloody flux, the sciatica, the trembling of any member, the bursting. Washe the mouth with the same herbs sodden in vinegar, it will ease the pain of the teethe. The green seed and dry also broken, health freckles and foule spots, when they be anointed therewith in the sun. They that are anointed with the same, with oil and vinegar are in no danger to be bitten of venomous beasts. It is good against the bloody flux, vomiting of blood, the common flux. The same seed sodden in water and vinegar or in wine is drunken against all the stinging of bees, wasps and such other like. The leaves with a little oil are laid on biting’s and burnings. It is evidently known that water will were thick if this root be bruised and put in, so that water stand abroad in the air without the doors. |

|

Of Marierum gentle. Marierum is called in Greke samsychos and amarokos, in latin amaracus or maiorana, in duche meieran of maioran, in French maiolayn or maron, some call this herbe in englysh merierum gentle, tot put a difference between an other herbe called mezierum, which is but a bastard kynde, this is the true kynde. Merierum is a thicke and bushy herbe creping by the ground with leves lyke small calaminte roughe and rounde. It hath lytle toppers in the hyest parte of the stalke muche lyke scales one growinge over another as the fyr tree nuttes do appere., It hath a very good savour. The vertues. The broth of thys herbe drunken is good for the dropsye in the begynnyng, and for them that can not make water, for the gnawing in the belly. The drye leves layd to, with hony take away blew markes, which come of beting, and in a supposytorye, they brynge doune wymens sycknes. They are also good to be layd unto the styngyng of a scorpyone with salt and vinegre. The same received in to a salve made of wex are good for lose swellings, and the are layd unto the eyes with the floure of barley, when they have inflammation. They are mixed with medycynes, which refreshe Merynes ans such emplasteres as are appointed to hete. The pouder of the drye herbe put in a mannes nose, maketh him to nese, the oyle that is made of merierum, warmeth and fasteneth the synoes. Thys herbe is hote in the thyrde degree, and drye in the seconde. |

Of Marjoram gentle. (Origanum majorana) Marjoram is called in Greek samsychos and amarokos, in Latin amaracus or maiorana, in German meieran of maioran, in French maiolayn or maron, some call this herb in English marjoram gentle, tot put a difference between another herb called marjoram, which is but a bastard kind, this is the true kind. Marjoram is a thick and bushy herb creping by the ground with leaves like small calamint rough and round. It hath little toppers in the highest part of the stalk much like scales one growing over another as the fir tree nuts do appear. It hath a very good savor. The virtues. The broth of this herb drunken is good for the dropsy in the beginning and for them that cannot make water, for the gnawing in the belly. The dry leaves laid to with honey take away blue marks, which come of biting and in a suppository, they bring down women’s sickness. They are also good to be laid unto the stinging of a scorpion with salt and vinegar. The same received into a salve made of wax are good for lose swellings, and they are laid unto the eyes with the flower of barley, when they have inflammation. They are mixed with medicines which refreshes medicines and such plasters as are appointed to hot. The powder of the dry herb put in a man’s nose maketh him to nose, the oil that is made of marjoram, warmth and fastened the sinews. This herb is hot in the third degree, and dry in the second. |

|